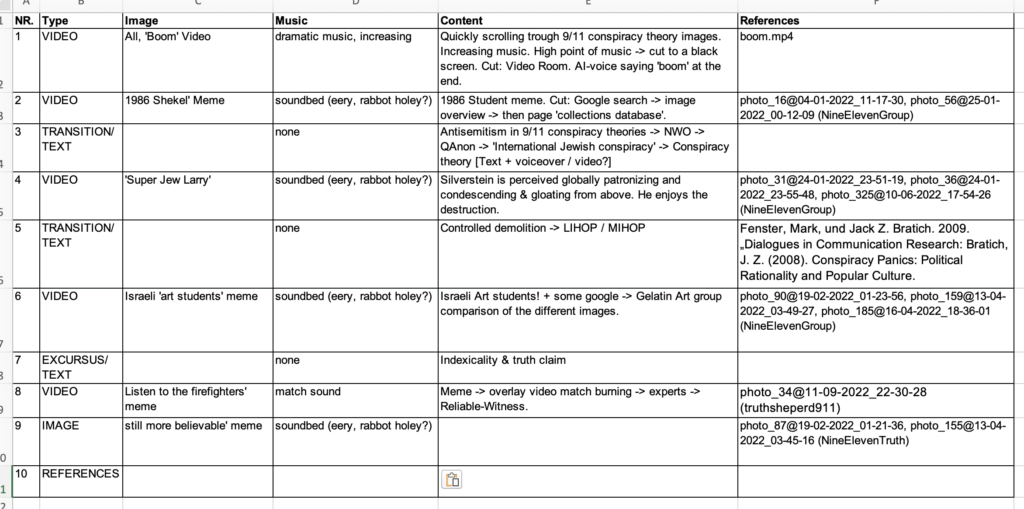

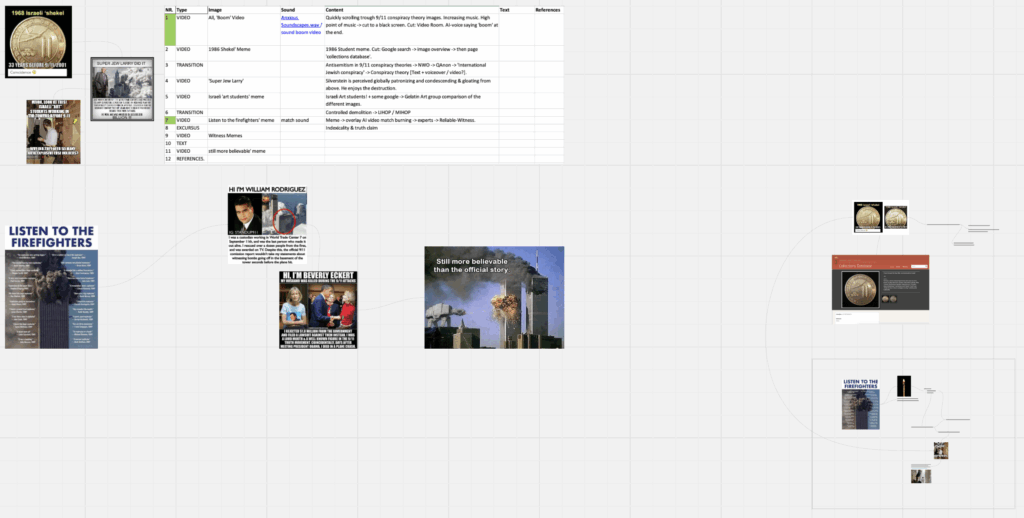

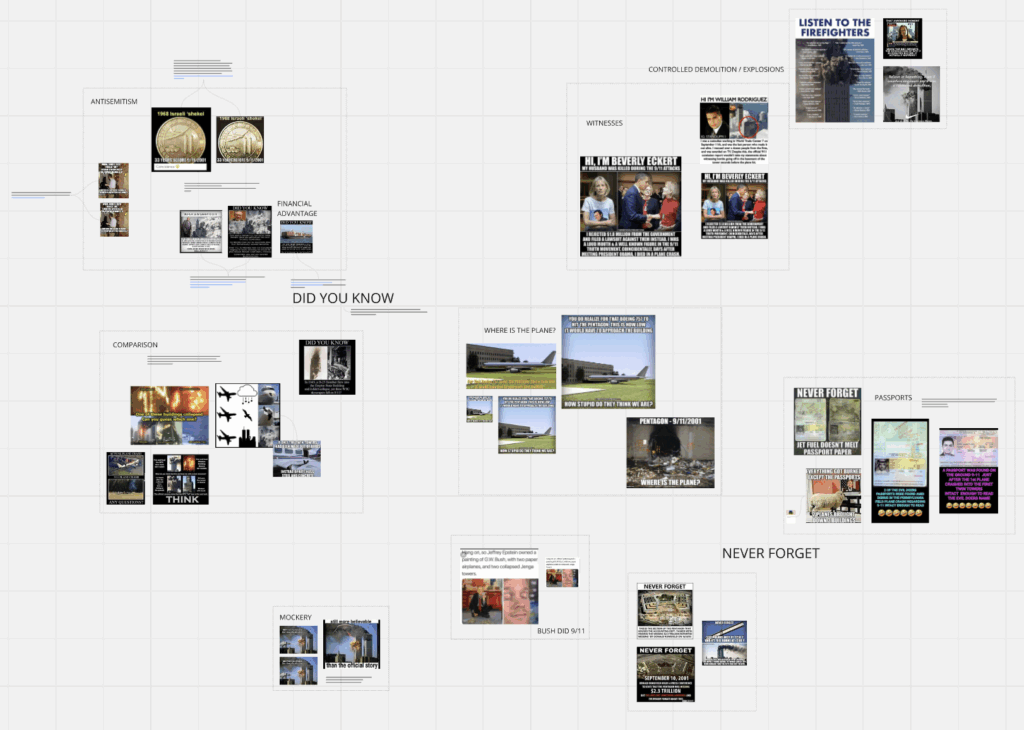

MEME RABBIT HOLES

Why Are Conspiracy Theories Often Antisemitic?

A conspiracy theory has three main characteristics: There are no coincidences, nothing is as it seems, and everything is connected. Further, conspiracy theories rely on the idea that a small, hidden group manipulates world events. Since medieval times, Jews have been falsely accused of playing this role. This myth was reinforced by fabricated texts like The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which falsely claimed Jews were plotting global domination. Even though The Protocols has been debunked, its themes persist in modern conspiracy thinking.

Antisemitic conspiracy theories often follow the same pattern: they present Jewish people as an all-powerful force behind economic collapses, wars, and political crises. This pattern is visible in 9/11 conspiracy theories as well as in claims about a “New World Order” or COVID-19.

The “New World Order” theory or NWO – The false belief that Jewish elites, especially the Rothschild family, secretly control world politics and finance.

Antisemitic Myths in 9/11 Conspiracy Theories

After the 9/11 attacks, many conspiracy theories emerged, some of which blamed Jews or Israel. Certain narratives gained traction, including:

• The “4,000 Jews didn’t go to work” myth – This false claim suggests that Jewish people had foreknowledge of the attack and deliberately avoided the World Trade Center that day. Despite being debunked, this myth persists in extremist circles.

• The “Mossad did it” theory – Some falsely argue that Israel’s intelligence agency, Mossad, orchestrated 9/11 to push the U.S. into Middle Eastern wars. -> LIHOP

• The “Jewish media cover-up” theory – This builds on the old antisemitic stereotype that Jewish-owned businesses and media outlets manipulate global events.

These claims fit into a broader historical trend: whenever a major crisis occurs, Jewish people are blamed. Similar accusations were made during the Black Death in the 14th century and economic recessions in modern times.

Why Do People Believe These Theories?

Psychological research suggests that conspiracy theories appeal to people for several reasons. Conspiracy theories are a simple answer to complex events. They provide an easy scapegoat. Further, People who are skeptical of governments and media are more likely to believe alternative narratives like conspiracy theories. Those with antisemitic beliefs are more likely to accept conspiracy theories that reinforce their biases.

The Real-World Impact of These Theories

Conspiracy theories are not just harmless speculation—they contribute to real-world harm. Such narratives often serve as a gateway to more extreme beliefs, radicalizing individuals and fueling discrimination. They have led to an increase in antisemitic hate crimes and violence, as well as the spread of misinformation.

The link between conspiracy theories and antisemitism is not accidental—it is part of a long history where Jewish people have been unfairly blamed for major events. Whether in 9/11 conspiracies or more recent theories about COVID-19, these narratives reinforce dangerous stereotypes.

References:

„Cincinnati Judaica Fund“, accessed March 18, 2025, https://www.cincinnatijudaicafund.com/Detail/objects/2301/representation_id/7647.

Michael Barkun, A Culture of Conspiracy : Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America, vol. Second edition, Comparative Studies in Religion and Society (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

Jovan Byford, “Conspiracy Theory and Antisemitism,” in Conspiracy Theories: A Critical Introduction, ed. Jovan Byford (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2011), 95–119, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230349216_5.

Alexis Chapelan, “Conspiracy Theories,” in Decoding Antisemitism: A Guide to Identifying Antisemitism Online (Springer Nature Switzerland Cham, 2024), 175–90, https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/94596/1/978-3-031-49238-9.pdf#page=182.

Peter Knight, “Outrageous Conspiracy Theories: Popular and Official Responses to 9/11 in Germany and the United States,” New German Critique, no. 103 (2008): 165–93.

Expanding the Conspiracy: From Who Planned It to How It Happened

Many conspiracy theories exist about the 9/11 attacks. Some include openly antisemitic claims. These suggest Jewish elites planned the attacks as part of a „New World Order“ agenda. Others focus on technical aspects, like how the Twin Towers collapsed.

One of the most common theories involves controlled demolition. This theory claims the World Trade Center towers didn’t fall because of the airplane impacts and fires. Instead, it suggests someone planted explosives in the buildings beforehand.

LIHOP: Let it happen on purpose.

MIHOP: Made it happen on purpose.

This idea belongs to the „Made It Happen On Purpose“ (MIHOP) framework. MIHOP theories claim certain actors actively planned the attacks. This goes beyond „Let It Happen On Purpose“ (LIHOP) theories, which suggest officials knew about the attacks but didn’t stop them.

The controlled demolition theory contradicts official findings. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) investigated the collapses thoroughly. They concluded that structural failures caused by intense fires led to the buildings‘ collapse.

See also: Jet Fuel Can’t Melt Steel Beams.

S Shyam Sunder et al., “Final Report on the Collapse of the World Trade Center Towers : Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster,” 0 ed. (Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2005), https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.NCSTAR.1;

Steve Clarke, “Conspiracy Theories and the Internet: Controlled Demolition and Arrested Development,” Episteme 4, no. 2 (June 2007): 167–80, https://doi.org/10.3366/epi.2007.4.2.167;

Michael J. Wood and Karen M. Douglas, “‘What about Building 7?’ A Social Psychological Study of Online Discussion of 9/11 Conspiracy Theories,” Frontiers in Psychology 4 (2013): 409, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00409.

“Jet Fuel Can’t Melt Steel Beams | Know Your Meme,” accessed March 31, 2025, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/jet-fuel-cant-melt-steel-beams.

Photography as evidence: from indexicality to virtual eyewitnessing

What is indexicality?

Why is photography considered evidence?

Photographs are considered evidence because of this diçrect connection between image and reality. They seem to say: „That is what really happened!“ Photographs are considered objective because a camera is seen as a neutral, mechanical witness, free from human bias or error.

But this idea of photographic truth is problematic:

1. Photos can be manipulated (in the past in the darkroom, today with Photoshop)

2. The photographer deliberately chooses the detail, perspective and moment

3. The interpretation of images is influenced by culture

Despite these limitations, photos have a strong emotional and convincing effect. They make us feel like we were there and see things with our own eyes.

Virtual eyewitnesses

Historian Andrew McKenzie-McHarg came up with the idea of „virtual eyewitnessing“ to explain how images play a role in conspiracy theories.

1. mediated experience: images allow people to „witness“ historical events even though they were not physically present. For example, millions of people watched 9/11 on TV and felt like they were witnessing it live, even though they only saw images.

2. self-empowerment through image analysis: conspiracy theorists encourage viewers to think like investigators by looking for strange details in images. They ask, „Look closely — what do you see that others miss?“

3. Community building: By analyzing and sharing images together, people create a community of „virtual eyewitnesses“ who believe they can see the „real“ story behind official depictions.

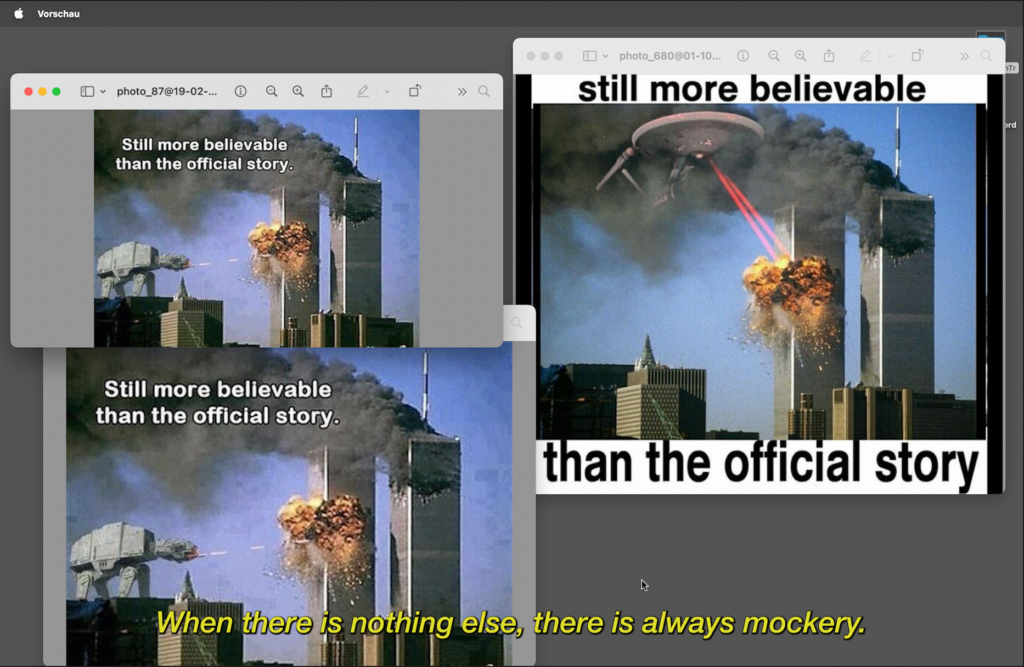

How memes use and reinforce these mechanisms

Memes about 9/11 and other controversial events are particularly powerful because they:

– They translate complex theories into simple, memorable images.

– They trigger emotions such as outrage or skepticism.

– They spread quickly and create a community of „knowers.“

– They often decontextualize or manipulate original images.

In the digital world, the original meaning of photographs is increasingly undermined, while at the same time the persuasive power of images as supposed evidence remains. This is a paradox that conspiracy theories exploit particularly successfully.

Roland Barthes, Die helle Kammer, 1. Aufl., Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1989);

Charles Sanders Peirce, “Ikon, Index Und Symbol,” in Diagrammatik-Reader. Grundlegende Texte Aus Theorie Und Geschichte, ed. Birgit Schneider (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Inc, 2016), 55–57;

Andrew McKenzie-McHarg, “Experts versus Eyewitnesses. Or, How Did Conspiracy Theories Come to Rely on Images?,” Word & Image 35, no. 2 (2019): 141–58, https://doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2018.1553388;

Tom Gunning, “What’s the Point of an Index? Or, Faking Photographs,” Nordicom Review 25, no. 1–2 (2004): 39–49, https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0268;

Walter Benjamin, “Das Kunstwerk Im Zeitalter Seiner Technischen Reproduzierbarkeit,” in Medienästhetische Schriften, ed. Detlev Schöttker, 4. Auflage, Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft 1601 (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2018), 351–83;

Sebastian Gerth, “Auf Der Suche Nach Visueller Wahrheit,” IMAGE. Zeitschrift Für Interdisziplinäre Bildwissenschaft. 27, no. 1 (2018): 5–23, https://doi.org/10.25969/MEDIAREP/16426;

Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, Penguin Books Non-Fiction (London; New York; Victoria: Penguin Books, 2004);

Madeline Ferretti-Theilig, “Fototheorie Neu Denken – Oder Die Rehabilitation von Relationalität in Der Fotografie,” in Beziehungsweisen Und Bezogenheiten. Relationalität in Pädagogik, Kunst Und Kunstpädagogik, vol. 4, IMAGO. Kunst.Pädagogik.Didaktik (kopaed, 2017), 407–28;

Peter Holzwarth, “Fotografische Wirklichkeitskonstruktion Im Spannungsfeld von Bildgestaltung Und Bildmanipulation,” MedienPädagogik: Zeitschrift Für Theorie Und Praxis Der Medienbildung 23, no. Visuelle Kompetenz (August 2013): 1–22, https://doi.org/10.21240/mpaed/23/2013.08.09.X;

Wolfgang Kemp, Geschichte der Fotografie: von Daguerre bis Gursky, 2. Aufl., Orig.-Ausg, Beck’sche Reihe C. H. Beck Wissen 2727 (München: Beck, 2014).

At the bottom of the rabbit hole? Or at the top?

Our exploration of 9/11 conspiracy theory memes reveals powerful mechanisms that spread alternative narratives through digital culture.

Photographs retain persuasive power despite our awareness of possible manipulation. The concept of „virtual eyewitnessing“ invites viewers to become investigators, creating communities of believers who feel they’ve uncovered hidden truths through image analysis.

Many of these conspiracy theories, as seen in the „Super Jew Larry“ and „Israeli art students“ examples, incorporate antisemitic tropes that follow ancient patterns of scapegoating. These narratives embody the conspiracy theory framework: „nothing is as it seems,“ „there are no coincidences,“ and „everything is connected.“

The memes employ sophisticated strategies — appealing to trusted authorities like firefighters, manipulating emotional responses through iconic imagery, and decontextualizing information to bypass critical thinking.

The real-world impact of these theories extends beyond academic interest. They contribute to misinformation ecosystems that can lead to radicalization and discrimination, with antisemitic elements directly contributing to hate speech and violence against Jewish communities, as well as other minorities.

This project demonstrates how artistic approaches can illuminate complex social phenomena. By understanding how conspiracy memes transform photographs into „evidence“ through manipulation and recontextualization, we gain insight into the broader challenges of navigating truth in our digital age.

Thank you for following me down this rabbit hole.

This site is an artistic work within the Web Residencies programme by Akademie Schloss Solitude.

© 2025. Akademie Schloss Solitude – Stiftung des öffentlichen Rechts, Stuttgart and Anne Braune

Literature

Barkun, Michael. A Culture of Conspiracy : Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. Vol. Second edition. Comparative Studies in Religion and Society. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

Barthes, Roland. Die helle Kammer. 1. Aufl. Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1989.

Benjamin, Walter. “Das Kunstwerk Im Zeitalter Seiner Technischen Reproduzierbarkeit.” In Medienästhetische Schriften, edited by Detlev Schöttker, 4. Auflage., 351–83. Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft 1601. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2018.

Byford, Jovan. “Conspiracy Theory and Antisemitism.” In Conspiracy Theories: A Critical Introduction, edited by Jovan Byford, 95–119. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230349216_5.

Chapelan, Alexis. “Conspiracy Theories.” In Decoding Antisemitism: A Guide to Identifying Antisemitism Online, 175–90. Springer Nature Switzerland Cham, 2024. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/94596/1/978-3-031-49238-9.pdf#page=182.

“Cincinnati Judaica Fund.” Accessed March 18, 2025. https://www.cincinnatijudaicafund.com/Detail/objects/2301/representation_id/7647.

Clarke, Steve. “Conspiracy Theories and the Internet: Controlled Demolition and Arrested Development.” Episteme 4, no. 2 (June 2007): 167–80. https://doi.org/10.3366/epi.2007.4.2.167.

Ferretti-Theilig, Madeline. “Fototheorie Neu Denken – Oder Die Rehabilitation von Relationalität in Der Fotografie.” In Beziehungsweisen Und Bezogenheiten. Relationalität in Pädagogik, Kunst Und Kunstpädagogik, 4:407–28. IMAGO. Kunst.Pädagogik.Didaktik. kopaed, 2017.

Gerth, Sebastian. “Auf Der Suche Nach Visueller Wahrheit.” IMAGE. Zeitschrift Für Interdisziplinäre Bildwissenschaft. 27, no. 1 (2018): 5–23. https://doi.org/10.25969/MEDIAREP/16426.

Gunning, Tom. “What’s the Point of an Index? Or, Faking Photographs.” Nordicom Review 25, no. 1–2 (2004): 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0268.

Holzwarth, Peter. “Fotografische Wirklichkeitskonstruktion Im Spannungsfeld von Bildgestaltung Und Bildmanipulation.” MedienPädagogik: Zeitschrift Für Theorie Und Praxis Der Medienbildung 23, no. Visuelle Kompetenz (August 2013): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.21240/mpaed/23/2013.08.09.X.

“Jet Fuel Can’t Melt Steel Beams | Know Your Meme.” Accessed March 31, 2025. https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/jet-fuel-cant-melt-steel-beams.

Kemp, Wolfgang. Geschichte der Fotografie: von Daguerre bis Gursky. 2. Aufl., Orig.-Ausg. Beck’sche Reihe C. H. Beck Wissen 2727. München: Beck, 2014.

Knight, Peter. “Outrageous Conspiracy Theories: Popular and Official Responses to 9/11 in Germany and the United States.” New German Critique, no. 103 (2008): 165–93.

McKenzie-McHarg, Andrew. “Experts versus Eyewitnesses. Or, How Did Conspiracy Theories Come to Rely on Images?” Word & Image 35, no. 2 (2019): 141–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2018.1553388.

Peirce, Charles Sanders. “Ikon, Index Und Symbol.” In Diagrammatik-Reader. Grundlegende Texte Aus Theorie Und Geschichte, edited by Birgit Schneider, 55–57. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Inc, 2016.

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. Penguin Books Non-Fiction. London; New York; Victoria: Penguin Books, 2004.

Sunder, S Shyam, Richard G Gann, William L Grosshandler, H S Lew, Richard W Bukowski, Fahim Sadek, Frank W Gayle, et al. “Final Report on the Collapse of the World Trade Center Towers : Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster.” 0 ed. Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2005. https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.NCSTAR.1.

“The B-Thing | Gelitin.Net.” Accessed March 31, 2025. https://www.gelitin.net/projects/b-thing/.

Wood, Michael J., and Karen M. Douglas. “‘What about Building 7?’ A Social Psychological Study of Online Discussion of 9/11 Conspiracy Theories.” Frontiers in Psychology 4 (2013): 409. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00409.

Images

All images used in the videos are from Telegram, @NineElevenTruth and @truthsheperd911. 2022.

Music

Match.wav by RynoStols — https://freesound.org/s/326727/ — License: Attribution NonCommercial 4.0

Ukelele drone.wav by robyn.levy323 — https://freesound.org/s/519231/ — License: Creative Commons 0

Anxious Soundscapes.wav by The_Runner_01 — https://freesound.org/s/561162/ — License: Creative Commons 0

horror ambiance 4430 150329_01 track 110 by klankbeeld — https://freesound.org/s/784344/ — License: Attribution 4.0

horror ambiance 4430 150329_01 track 110 by klankbeeld — https://freesound.org/s/784344/ — License: Attribution 4.0

DSGNRise_Dark TV Abyss.Ver. 5_EM by newlocknew — https://freesound.org/s/790218/ — License: Attribution NonCommercial 4.0

DSGNRise_Dark TV Abyss.Ver. 5_EM by newlocknew — https://freesound.org/s/790218/ — License: Attribution NonCommercial 4.0